Like Traditional Chinese Medicine and acupuncture, the true origins of T’ai Chi Chuan dates back to a time before written history. Cave paintings in China show exercises similar to t’ai chi known as ‘Tao Yin’ appearing as early as 3000 BC during the reign of China’s mythical first emperor, Fu Hsi. If the origins of t’ai chi are steeped in mystery and legend,[1] making it difficult to pin down a precise point of “where and when t’ai chi began”. We do know that during the Sung Dynasty (960-1279 C.E) Master Chen Tuan (ca. 885-989) revived the aspects of martial arts and philosophy and called it T’ai Chi.[2]

The earliest silk painting (100 x 50 cm) featuring Tao Yin

from No. 3 Mawangdui Tomb in Changsha

depicting 44 men and women of all ages flexing, stretching, jumping and turning around.

The common legend at the first ‘emergence’ of t’ai chi chuan is in the obscure personage of Chang San-feng[3] who lived towards the end of the Sung Dynasty (13th century). Described as an eccentric, itinerant hermit with magic powers, Chang San-feng is an obscure semi-mythical figure because there is speculation as to whether he was an actual person or simply a literary creation though he is occasionally referred to as the “father of t’ai chi”. Although many scholars and historians contend his existence, it seems there is much evidence about his activities to disregard him as an entity of fiction.[4] His exact dates vague but we do know he was canonised in 1459 by the Emperor Ying Zong (1436-1464). Two huge stone tablets honour him as a Taoist saint and the 9th of April is celebrated every year as the day he was born. He was known by many different names. It is the general consensus that he was first trained as a Shaolin monk left to train with the Taoist Master Fire Dragon at Nanshan Mountain in Shenxi. He then cultivated his spiritual development for nine years in the Wudang Mountains where he acquired his Taoist name of San-feng.[5] The earliest reference to Chang San-feng as an ‘internal martial artist’, emphasising the practice of breath control, qi channelling and visualisation (as opposed to ‘external’ style of Shaolin, the traditional Buddhist martial arts), refers him as a boxing master.[6]

creation though he is occasionally referred to as the “father of t’ai chi”. Although many scholars and historians contend his existence, it seems there is much evidence about his activities to disregard him as an entity of fiction.[4] His exact dates vague but we do know he was canonised in 1459 by the Emperor Ying Zong (1436-1464). Two huge stone tablets honour him as a Taoist saint and the 9th of April is celebrated every year as the day he was born. He was known by many different names. It is the general consensus that he was first trained as a Shaolin monk left to train with the Taoist Master Fire Dragon at Nanshan Mountain in Shenxi. He then cultivated his spiritual development for nine years in the Wudang Mountains where he acquired his Taoist name of San-feng.[5] The earliest reference to Chang San-feng as an ‘internal martial artist’, emphasising the practice of breath control, qi channelling and visualisation (as opposed to ‘external’ style of Shaolin, the traditional Buddhist martial arts), refers him as a boxing master.[6]

There are several legends which date from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644): one says Chang San-feng created t’ai chi chuan in his dreams;[7] another states that he created it by observing monks boxing on Wudang Mountains.[8] However, the legend that seems to have inspired and influenced practitioners of t’ai chi chuan is the event when, whilst meditating, his attention was attracted by the strange cry of a crane which had been frightened by a snake. A combat took place over a morsel of food. On seeing this fight, Chang San-feng was inspired by the distinctive qualities of both animals during this fight: the qualities of the snake related to speed, awareness, flexibility and curvilinear movements, and the qualities he observed in the crane, those of a unique sense of balance, gracefulness and its strength through softness. Finding this fight inspiring, it is said he integrated what he learned from these fighting movements into his practice and developed the art of Bagua (Pa Kua).

The importance of Chen Wang-t’ing (1580-1660) is that he is the first historically verifiable originator of t’ai chi chuan. When the peaceful and prosperous Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) was replaced by the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), Chen Wang-t’ing, a ninth-generation Chen patriarch, scholar and Ming military officer, retired from government service. It is at this time that he developed the art of t’ai chi chuan by integrating different elements of Chinese philosophy into the martial arts he learned from his army general, the great Ch’i Chi-guang (1528-1588) who wrote The Classic of kungfu or Boxing Classic (1559-61). Chen Wang-t’ing’s style combined jumps, leaps and explosion of strength together with some yin and yang principles, techniques found in Tuina and in theories encountered in Traditional Chinese Medicine. He is also credited with the invention of the first pushing hand exercises.

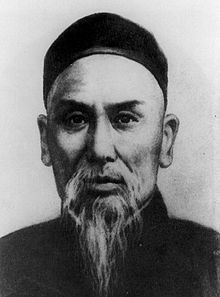

A student from a poor family, Yang Lu-ch’an (1799-1872) represents a pivotal turning point in the history of t’ai chi. He lived in Chen village and worked for Chen Chang-hsing’s on the farm. Not belonging to the Chen family, he watched secretly the t’ai chi practices. One day he offered to fight a stranger who had challenged Chen Chang-hsing. Yang fought so well that, in 1820, Chen accepted Yang as a student and taught him all the skills, techniques and secrets of the Chen style of t’ai chi. More significantly, Chen gave Yang Lu-ch’an permission to travel China as a Chen family representative offering challenges to fighters so successfully that he earned the title of ‘Yang Wudi’, meaning Yang the invincible. As a result, he was appointed to teach Chen style t’ai chi to the Imperial Guards and members of the Ch’ing court in Beijing. Thus he became the first outsider to break the tradition of restricting Chen style t’ai chi chuan to Chen family members only. His subsequent expression of t’ai chi chuan became known as the Yang style, the most widely practised style in the world today. His approach aimed at a less laborious routine with less emphasis on martial applications thus adapting the growing public’s interest for better health and personal development.

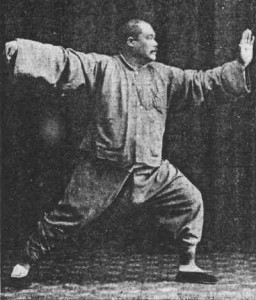

Yang Cheng-fu (1883-1936), the grandson of Yang Lu-ch’an, introduced what may be called ‘Modern T’ai Chi’. As with all the t’ai chi styles, the Yang style went through several developments: Yang Chen-fu eliminated the foot-stamping, straight-punching, jumping and other forceful, aggressive actions which are more appropriate for combat. He then adapted his style according to his large frame by  making the movements bigger, smoother and rounder, slow, continuous and harmonious, performed at a constant speed, so as to promote the health aspect of

making the movements bigger, smoother and rounder, slow, continuous and harmonious, performed at a constant speed, so as to promote the health aspect of

t’ai chi chuan. Cheng-fu passed the skill on to Yeung Sau-chung (1910-1985), the only one of his sons old enough to have developed sufficient skill. Sau-chung settled in Hong Kong after the Communist revolution and after having 3 daughters he decided to adopt 3 sons to carry on his teaching. They were Ip Tai Chi Tak, Chu Gin Soon and Chu King Hung.

Despite variations in form and technique, the underlying concepts set out in the “T’ai Chi Classics” of relaxed, whole body power and the avoidance of using force against force, are the foundations of all styles of t’ai chi chuan. Each style was named after their founders, Chen, Sun, Wu, Hao and Yang:

- The Yang Style (founded by Yang Lu-ch’an, 1799-1872) is the most popular of all the styles which aims at balancing the qi flow through inner structural alignment and stillness within movement, at strengthening and relaxing the mind and body, and at living in harmony with the yin and yang cycles found in nature.

- The Chen style (created by Chen Wang-t’ing, 1580-1660) is the oldest and parent form of the five main t’ai chi chuan styles. It is characterized by its lower stances, ‘silk reeling’ and bursts of power (fa jin).

- The Wu style (founded by Wu Chien-ch’uan, 1870-1902) is distinctive in its small circle hand techniques, pushing hands and weapons training that emphasises parallel footwork and horse stance training with the feet relatively closer than the Yang or Chen styles.

- The Sun style (created by Sun Lu-t’ang, 1861-1932) combines 3 styles of t’ai chi movements together: the Wu style with elements of Hsing-i and Bagua, giving its Form small, smooth, flowing movements (performed with open palms) which omits the more physically vigorous crouching and leaping of some other styles.

- The Wuu/Hao (founded by Wu Yu-hsiang, 1812-1880) is an uncommon style today that has small, subtle movements, highly focused on balance, sensitivity and internal chi

[1] In ancient China it was imperative that families kept their secrets close at heart

[2] Hua-Ching Ni, Strength from Movement – Mastering Chi, [Tao of Wellness Press, SevenStar Communications, 2009], p. 129

[3] He was known by many names: Chang San-Feng, Cheng San Feng, Chang Chun Pao, Chang Sam Bong, Zhang Sanfeng, Chang Tung, Chang Chun-pao, Grandmaster Chang, Chang the Immortal, Immortal Chang, Zhangsanfeng, Zhan Sa-Feng, Zhan Jun-Bao, Yu-Xu Zi, Chuan Yee and Chun Shee.

[4] He is recorded by reliable historical documents such as the Ming History and The Ningpo Chronicles – which have no relation to martial arts literature – as having existed and to have created the ‘Wudang Internal Boxing arts’.

[5] The Wudang Mountains have many Taoist temples, monasteries and have been renowned as academic centres since 700 CE. They have long been associated with Taoist studies and practices, Taoist scriptures, Traditional Chinese Medicine, herbal research, agricultural arts, meditation, unique exercises to increase longevity and internal martial arts.

[6] Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan (1669), composed by Huang Zongxi (1610-1695 AD).

[7] Whilst Chang San-feng was seeking the fabled elixir of life, a liquid formula that reputedly makes one immortal, the movements of T’ai Chi Chuan were revealed to him in a dream.

[8] He observed that they used too much force and outer power that made them lose their balance. He thought that if yin and yang were balanced inside their body they would be less inept. Hence he understood the supremacy of flexibility on rigidity, the importance of the alternation of yin and yang concepts that form the basis of t’ai chi.